The Racial Divide in Feminism

Written by: Ajeé Buggam

The divide between Black and white feminists in America has occurred since chattel slavery and continues to the present day. During slavery, Black women weren’t treated as human — their bodies were utterly objectified and many white women justified the molestation, rape, and physical violence of Black women at the hands of white slave owners. To this day, white women’s cries get more attention and response than Black women’s pain.

Film and television has historically contributed to negative representations of Black women. Authors, Goldman and Waymer mention, “The uniqueness of the Black woman is that she stands in the crossroads of two of the most well-developed ideologies in America regarding women and regarding the negro.” Black women have been limited to discouraging roles, limited to specific character traits where they are left to fight life battles independently, such as the strong Black woman who provides self-sacrificial strength while offering endless support to her loved ones.

In bell hook’s book, “Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism,” she mentions, “When feminists acknowledge in one breath that Black women are victimized and in the same breath emphasize their strength, they imply that though Black women are oppressed, they manage to circumvent the damaging impact of oppression by being strong — and that is simply not the case.”

Little Fires Everywhere by Celeste Ng (Photo by Cassidy)

Hulu’s show Little Fires Everywhere, an adaptation of the bestselling novel by Celeste Ng, highlights the divide in feminism within Elena and Mia’s relationship, which was forced from the beginning of the show. Elena is a middle class white woman, a long time Shaker Heights resident, journalist at a local paper, mother of 4 children, married to a successful lawyer, and — more than anything — a perfectionist. On the contrary, Mia is a Black woman in the working class where she makes her living as a brilliant artist, single parent to Pearl, and is very free-spirited.

Throughout the show, Elena made many gestures to help Mia by renting her family’s property at a lower price, hiring her as a part-time housekeeper, and speaking up for Mia’s daughter about her incorrect placement for a math class. But what Elena doesn’t realize is that Mia was never looking for handout. She only agreed to work for Elena because she didn’t trust her and wanted to keep an eye on Pearl. Mia was also upset when she learned that Pearl told Elena about her placement issues for her math class.

Mia tried hiding her past in every way she could, and Elena did everything to dig it up and throw it in her face. Elena was oblivious to the damage she caused, thinking she was the hero, and didn’t make time to get to know Mia and understand her experiences. Mia barely had a chance to be vulnerable without judgment, a dynamic between many Black and white women. There are many assumptions, stereotypes, and implicit bias but little room for trust.

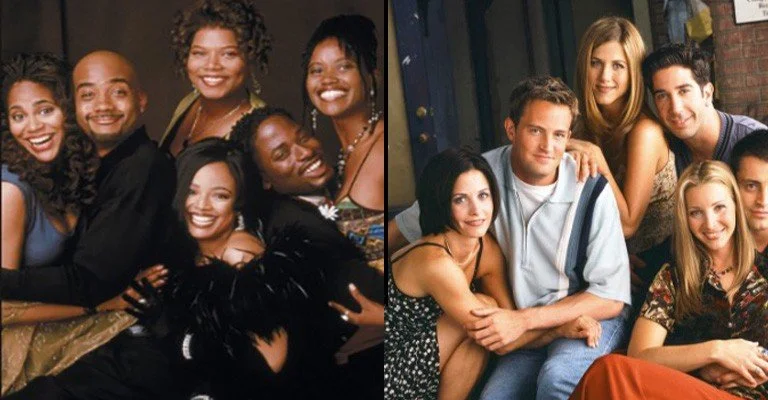

Another example between the divide in feminism was in the TV show, Black-ish. In the season 6 episode, “Feminisn’t,” Rainbow Johnson, played by Tracee Ellis Ross, is reunited with her best friends from the former CW show Girlfriends where she played attorney and, later, restaurant owner, Joan Clayton. Rainbow wants to add diversity to her local feminist group by bringing Jill Marie Jones, Golden Brooks, and Persia White, who played Toni, Maya, and Lynn in Girlfriends. It was all smiles and hugs, but when Jones’ character mentioned the difference between the wage gap for white women and Black women based on what white men made, odd looks were shared, but they made a new protest sign highlighting both pay gaps.

There was another conversation about a congressional seat opening soon and one of the Black women in their group should have that seat. Rainbow’s white feminist friend, Abby, mentions her irritation with Rainbow and her Black friends making this a “race thing” because the group was supposed to be about all women’s issues.

Rainbow explains how she cannot choose between, “being a woman and being Black.” Intersectional feminism, a term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, is the way Black women’s race and gender experiences overlap to form unique experiences with discrimination. “All inequality is not created equal,” says Crenshaw, “We tend to talk about race inequality as separate from inequality based on gender, class, sexuality, or immigrant status. What’s often missing is how some people are subject to all of these, and the experience is not just the sum of its parts.” Many white women don’t want to recognize that race is always involved with politics — there is no separation — especially around gender equity issues. For every issue — workplace harassment, reproductive justice, education — there is an added layer of systemic racism that further magnify inequities.

Until we’re able to recognize our significantly different struggles, no real change can come within the feminist movement. This is possible with more representation both on- and off-camera. We need more dialogue like that of Little Fires Everywhere and Black-ish, but we also need more Black women writers, producers, visionaries, creators, and directors across genres. When women like Issa Rae, Ava DuVernay, Michaela Coel, Robin Thede, Stella Meghie, among countless others are not only in positions to act but to tell our stories, Black women then have the power to control our narratives and shift perceptions about us in television and film.